Phone in the freezer: Using Phyphox to explore gas laws, thermodynamics, and energy efficiency

I’m a big fan of Phyphox, a free app for iOS and Android that lets you record raw data from your smartphone’s sensors. Smartphones have a mind-blowing array of sensors, including accelerometers, gyroscopes, magnetometers, and barometers. Some Android phones also have temperature, humidity, and proximity sensors. I love using Phyphox to perform little experiments, like mapping out the magnetic field lines near the MRI machine at UC Riverside’s Center for Advanced Neuroimaging, or measuring the rate of ascent of the Palm Springs Aerial Tramway by monitoring the barometric pressure inside the tram.

In case some of these little experiments might be useful for K-12 STEM teachers in their classrooms, I’ll share some of them here. Read on for a little middle- or high-school-targeted lesson that uses a smartphone and a freezer to explore principles of gas laws, thermodynamics, and energy efficiency…

The experiment

Today’s experiment uses the big upright freezer in my garage, which looks like this:

I started the barometer (air pressure) logger in Phyphox, then I placed my iPhone inside a big upright freezer in my garage and closed the door. I then waited for about a minute before opening the freezer door and retrieving my phone.

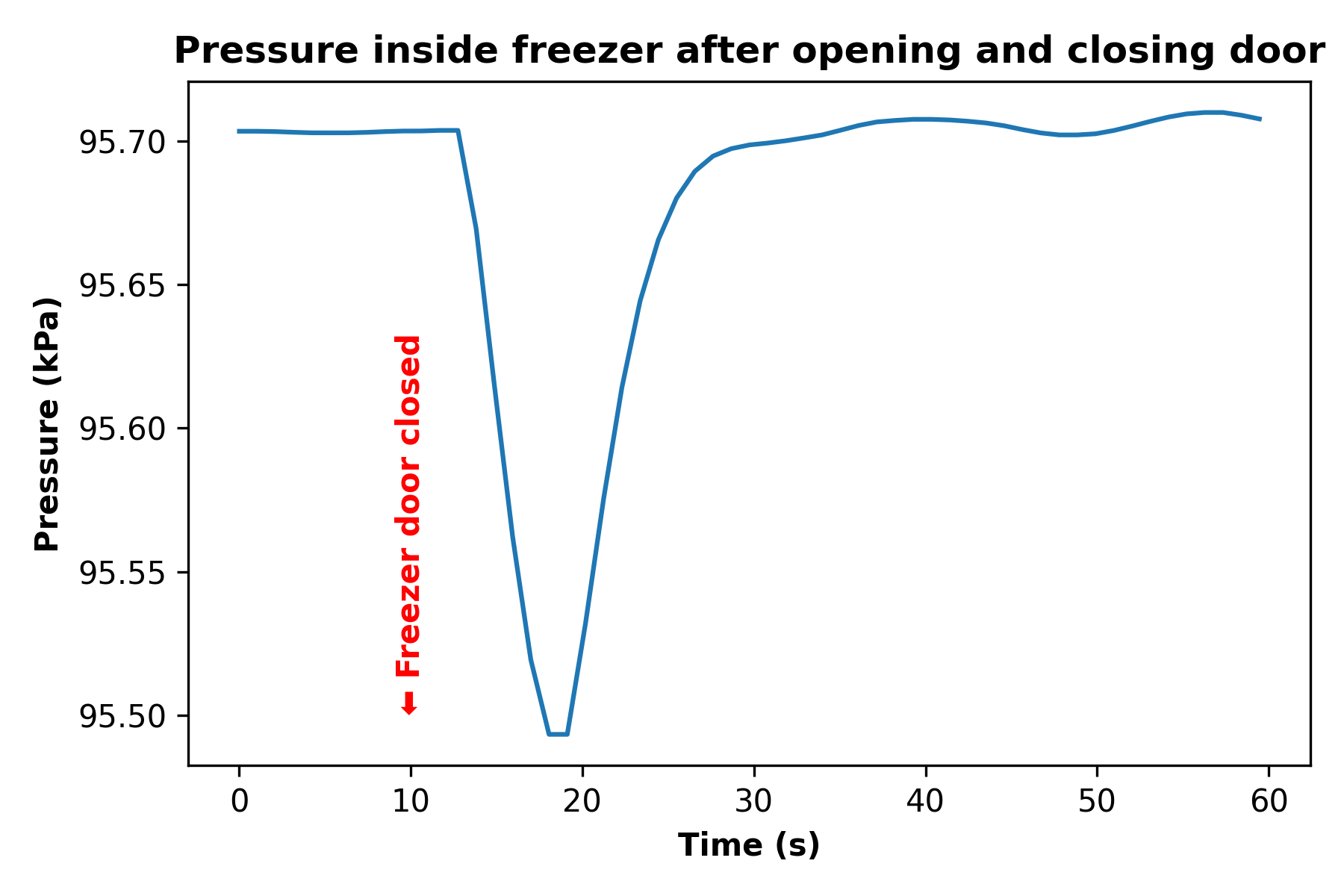

After exporting the barometer data from Phyphox and whipping up a quick Python program to plot it, here’s what I got:

What’s going on here?

The phenomenon

What is the phenomenon I observed that I’m trying to explain?

Looking at the data above, I marked in red the point at which I closed the freezer door with the phone inside, at the ten second mark. Within a couple seconds of closing the door, we see the air pressure inside the freezer drop from 95.70 kPa to 95.50 kPa. This is a relatively small change—just a 0.2% decrease—but it is easily detectible using my iPhone’s barometric pressure sensor. Then around the 20-second mark we see the air pressure inside the freezer start to rise again, reaching the starting pressure within about five seconds.

So that’s our phenomenon: we observed that after opening and closing a freezer door, the air pressure inside the freezer abruptly drops, then rises back to the starting pressure.

What’s happening?

This is the point where you might show your students this data (or better yet, have them recreate my experiment using their own phones and freezers and get their own data) and have them write in their notebooks possible explanations for what is causing the changes in the pressure inside the freezer. There are two distinct changes here—the decrease in pressure after the door is closed, and the increase in pressure after a little time passes—and we should have explanations for both of these changes. Students could then share their proposed explanations with the rest of the class and we can arrive at a consensus explanation.

Here’s my explanation:

This is an upright freezer that’s normally filled with cold air. When I opened the freezer door, a lot of that cold air slid down and out of the front of the freezer (because cold air is more dense than warm air) and was replaced by warm air from my garage. When I closed the freezer door, that new warm air is trapped in the freezer, and it quickly cools down. The amount of gas inside the freezer remains unchanged, but the temperature of the gas inside the freezer drops. The Gay-Lussac law and the ideal gas law tell us that if the volume of gas remains constant but the temperature drops, we expect the pressure to drop, and that’s exactly what our smartphone records in the first few seconds after closing the door!

So what causes the pressure to rise again a few seconds later? The seal on my freezer door isn’t perfect—it lets a little air pass between the outside and the inside of the freezer. So when the pressure inside the freezer drops to below atmospheric pressure, air from outside the freezer flows into the freezer until the pressures inside and outside of the freezer are equal again. In fact, if I listen closely, I can hear the “whoosh” of air flowing through little leaks in the door seal.

The engineering practice

Now let’s look at this phenomenon from a practical standpoint: we’re using my freezer to cool my garage air, which isn’t really optimal. Ideally, my freezer should be cooling my food, not my air! And that’s a jumping-off-point for a possible engineering practice in the classroom: how could you engineer a change in this setup to make my freezer more efficient? To not waste energy cooling air every time I open and close the freezer door?

One possible answer might be to make the seal around my freezer door better, so that no air flows into or out of the freezer when the door is closed. But this could have an unintended side effect: if the air inside the freezer stays at low pressure, it might become difficult for me to open the door! Let’s perform a little calculation. Our data shows that there’s a 0.20 kPa (or 200 Pa) pressure difference between the inside of the freezer and the outside. Remember that pressure units are force applied over a surface area. In the case of pascals, 200 Pa is 200 newtons of force applied over 1 square meter of surface area. Conveniently, my freezer door has a surface area of about 1 square meter, so we can estimate that the pressure difference between the inside and outside of my well-sealed freezer creates a force of about 200 newtons—this force is holding the door closed, so I’ll need to pull with about 200 newtons of force in the opposite direction to overcome the pressure difference and open the door. How much force is 200 newtons? We can use force = mass x acceleration (F = ma) to calculate how much mass (or weight) we’d need to hang from the door (presumably using a pulley) to open the door. Rearranging the equation to m = F/a, we determine m = 200 newtons / 9.8 m s^-2 = 20 kg of mass (or weight). That’s about 44 pounds that I’ll need to apply to the freezer door to overcome the pressure difference that’s holding it closed! That’s doable, but I’m not sure I want to pull 44 pounds every time I want a bowl of ice cream…

Another possible answer to the question “how can I stop my freezer from wasting energy cooling air?” is to get a different type of freezer. Specifically, I could get a chest freezer like the one shown here:

These freezers have some disadvantages—they take up more floor space, for example—but they have an enormous energy-efficiency advantage over upright freezers: the cold air doesn’t spill out of them when you open the door. That means that they don’t have to waste energy cooling a new volume of warm air every time you open the door. Here’s a quote from a University of California, Santa Barbara blog post about upright versus chest freezers:

“When the door is opened in an upright freezer, large sums of cold air are let out and heat is let in which draws more energy to re-cool the system. Whereas with a chest freezer, there is less cold air loss when the door is opened, the larger depth of the freezer also helps reduce cold air loss, resulting in less energy being needed to restabilize the cold temperature in the freezer.”

Those are two ideas for how to improve the energy efficiency of my freezer. What else can your students come up with? Model their proposed solutions in their notebooks!

In summary, we’ve gone from an observed phenomenon (the air pressure inside my freezer drops then rises whenever I open the door) to an explanation (gas density as a function of temperature, the ideal gas laws, and a leaky freezer door) and a modeling based engineering practice (brainstorming ways to improve the energy efficiency of my freezer), all thanks to Phyphox and my phone. Hopefully this experience (or something like it) can be useful in your STEM classroom!