The R.E.M. and James Agee story

A true story from my undergrad days at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

* * *

Back in college I got interested in Knoxville history, so it wasn’t long before I learned about James Agee. Agee was Knoxville’s greatest writer, his reputation only eclipsed by Cormac McCarthy’s stardom. Agee’s most famous work, A Death in the Family, was published after his death and earned him a posthumous Pulitzer Prize. Set in Knoxville in 1915, it tells the story of a boy whose father was killed in a car crash. The book was based on events in Agee’s own childhood in Knoxville, including his own father’s death when Agee was only six years old.

One day in 1995 I went to Hodges Library and checked out the library’s old hardcover copy of A Death in the Family and started reading it over dinner at Sophie’s cafeteria. I started reading the prose poem that opens the book:

“We are talking now of summer evenings in Knoxville, Tennessee, in the time I lived there so successfully disguised to myself as a child.”

I could see myself in that poem. I was a sophomore in college, trying to become my adult self, embracing things I’d tried to disguise as a child. In Agee’s memories of his own childhood, I saw reflections of my own. Not in the tragedy that comes later in the book, thankfully, but in the precocious and observant boy seeing and feeling so much beauty and sadness in absolutely everything, from the sound of a chorus of locusts to the shape of the water flowing from a garden hose. Toward the end of the poem, Agee describes lying in his backyard with his family:

“One is my mother who is good to me. One is my father who is good to me. By some chance, here they are, all on this earth; and who shall ever tell the sorrow of being on this earth, lying, on quilts, on the grass, in a summer evening, among the sounds of night.”

It was such a poignant scene, so familiar, so ephemeral, so visceral that you can feel and hear and smell it, so authentically Southern, and so true.

* * *

It was about this time that word came out in the Metro Pulse that R.E.M. was coming to Knoxville. Does everyone have a particular musical act that just speaks to them, like the band was writing the songs and lyrics just for them? That’s R.E.M. for me.

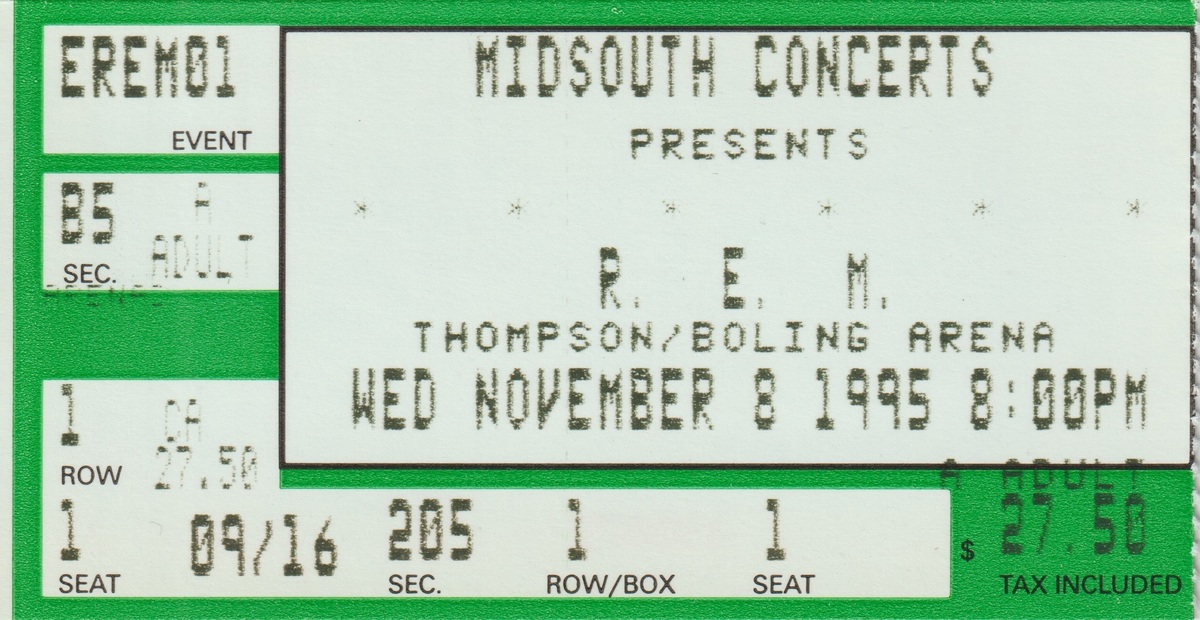

The Metro Pulse said that the show would be November 8, 1995, in UT’s Thompson-Boling Arena. Tickets would go on sale a few weeks before the show at Cat’s Records on Cumberland. And as was tradition back then, there would be people camping out to be first in line for the best seats.

When the day before the ticket sale came, I finished dinner and headed down to Cat’s. I brought a blanket and a pillow and A Death in the Family to read while I waited. I claimed a spot on the grimy Cumberland sidewalk—third in line—and settled in for the night. It was a terrible sleepless night, and when the sun finally rose and the Cat’s employee unlocked the door, I shuffled inside half-dead and stumbled to the cash register. I remember that the cashier was a little surprised that I’d gone to the trouble of camping out, only to purchase a ticket in the “cheap seats” instead of the more-expensive front-row seats that the other campers were buying.

My next memory was me tumbling into my bed in Hess Hall.

* * *

“Where’s the book?”

I woke up midday in a panic. I looked all around my tiny dorm room, but it wasn’t there. I retraced my steps in my mind. I had it on Cumberland, but I didn’t remember bringing it inside Cat’s, and it wasn’t here.

I must have left it on the sidewalk.

I ran down Melrose to Cumberland and Cat’s.

There was nothing there, just the same dirty sidewalk that I’d failed to sleep on the night before.

I went inside Cat’s and asked the same employee who’d sold me my ticket a few hours before. Had a book been turned in?

She looked under the counter. “Nope, no library books here,” she said.

I walked up and down the block a few more times, and searched the adjoining alleys too. No luck. Hodges Library’s copy of “A Death in the Family” was gone. I’d lost Agee’s book just a couple blocks from where he grew up, where the scenes in the book had actually occurred, where he and his mother and father had spent those evenings lying, on quilts, in the grass.

* * *

“How much would it cost replace a book I might have lost?” I asked the librarian at the Hodges check-out desk a few days later.

“Let me scan your card,” she said.

My face turned red with embarrassment. I felt like a child waiting to be scolded.

“Is it A Death in the Family? she asked.

“That’s right,” I said.

“It looks like replacing it would be around a hundred twenty-five dollars.”

“Oh,” was all I could manage.

The librarian must have seen the expression of pain on my face, because she explained, “It was hardcover… a special library binding… those can be a little expensive to replace.”

This was so much more than my R.E.M. ticket had cost. This was even more than the expensive front-row seats that I couldn’t afford.

“Well,” she said, “Give it some time. Sometimes lost books make their way back to the library.” I felt like throwing up.

“By the way” she said, “if you can find a hardcover copy of the book in good condition, we might be able to use that to replace the book.”

This gave me some hope. I enjoyed going to Knoxville’s used book shops and antique stores. Surely I could find a hardcover copy of James Agee’s book in his hometown for less than $125.

* * *

The next weekend I logged into the library’s website and viewed my account. It showed one book still checked out. A Death in the Family hadn’t been returned.

I walked from campus across Downtown to the Old City, where a couple of the old warehouses on Jackson had been turned into antique shops. I sifted through the stacks of old books and found a few paperback copies of Agee’s book, but no hardcovers.

I rode the KAT bus out Kingston Pike to McKay’s, which had secondhand copies of everything, it seemed, except for a hardcover Death in the Family.

For several weeks I repeated my search, casting a wider net, looking up antique stores and bookstores from Strawberry Plains to Farragut and calling them, and always coming up empty-handed.

Along the way, I found a few other books by (or about) James Agee, and I bought some of them—a paperback of his film scripts, another of his movie reviews, a slim book of his correspondence with a beloved teacher from his youth, a biography—none of them more than a couple dollars each. I read these and got to know this brilliant and flawed Knoxvillian who went on to Harvard and New York and Hollywood and worked and smoked and drank himself to death at just 45, leaving behind so much beauty but even more unfulfilled potential.

While I searched, I kept renewing the book loan on the library website, each time delaying the inevitable by a couple weeks. But as the weeks went by, I began to realize that hardcover copies of A Death in the Family were a lot rarer than I expected. And this was before eBay made it routine to buy used books from people on the other side of the planet.

I wasn’t going to be able to find a replacement copy of Agee’s book.

* * *

Finally, November 8 came, the night of the R.E.M. show. I went to Thompson-Boling Arena a little sad. This concert and the lost library book were inseparably linked now; I wasn’t sure if I could enjoy the former without thinking about the latter.

But when the lights went down and Peter Buck’s guitar rang out and Michael Stipe started singing, “‘What’s the frequency, Kenneth?’ is your Benzedrine, uh-huh,” all was forgotten. On to “Crush with Eyeliner” and “Turn You Inside-Out” and “Try Not to Breathe,” the show was electric and the audience rowdy and appreciative. From my spot at the very front of the cheap seats, I was enthralled.

But a few songs in, Michael Stipe stopped singing.

He mumbled something about “doing something he’d always wanted to do in Knoxville,” pulled out a book, and started reading out loud from it.

The crowd was still noisy, and no one could hear what Stipe was reading. After a few moments he seemed to realize this and looked up from his book and said sternly, “Do you mind?”

The crowd heard that. And after they grew quiet, Stipe restarted his reading:

“We are talking now of summer evenings in Knoxville, Tennessee, in the time I lived there so successfully disguised to myself as a child…”

These words, words that had meant so much to me when I first read them a few weeks earlier, words from the book I lost trying to get tickets to see this show, now read aloud by Michael Stipe in front of thousands of confused fans just a couple blocks from where James Agee had lived these words 80 years earlier…

By the time I recovered from the shock, Stipe was concluding,

“…and who shall ever tell the sorrow of being on this earth, lying, on quilts, on the grass, in a summer evening, among the sounds of night.”

Many songs later, after the traditional “End of the World as We Know It (And I Feel Fine)” finale, I walked back to my room in Hess Hall completely ecstatic. And I knew that it was time to settle my debt with the library.

Agee’s book deserved to be replaced.

* * *

The next morning I walked the short distance to Hodges Library and got in the check-out line. Soon it was my turn at the desk. I placed my ID card on the counter.

“I’d like to pay for a lost book,” I said.

The librarian scanned my card with her laser gun and looked at her computer screen. “What book?”

“James Agee,” I said, “A Death in the Family.” Hardcover, I said to myself. Special library binding. I felt for my wallet which I knew did not contain a hundred twenty-five dollars.

“That book was returned,” said the librarian.

“What?” I said, not sure I heard her correctly.

She leaned closer to the screen. “It looks like it was returned to the library… yesterday,” she said.

“So… wait,” I tried to find the right words, “I don’t owe anything? There’s nothing on my account?”

“Nope,” she said, “no loans, nothing checked out, you’re all good.” She glanced at the line behind me. “Is there anything else I can help you with?”

“No,” I said, “no, I’m all good,” and I walked back to my dorm room.

* * *

A decade later, while I was completing my Ph.D. thesis in Berkeley, I wanted to include a quotation in the beginning of my thesis that captured the complex mix of feelings that filled my head at that moment. I chose a quote that Michael Stipe and I both have a little history with:

“By some chance, here they are, all on this earth; and who shall ever tell the sorrow of being on this earth, lying, on quilts, on the grass, in a summer evening, among the sounds of the night.”