The rise (and risks) of resin-based 3D printers

Not long ago, 3D printers were so expensive and rare that the idea of having a 3D printer at home seemed like science fiction. But today I have a 3D printer in my garage. You can also find 3D printers at my son’s middle school, my public library, and in the homes of some of my bioengineering students at the University of California, Riverside, who are currently using their own 3D printers to build class projects while our campus is temporarily closed.

3D printers aren’t new—the first ones were produced decades ago. But the price of 3D printers has plummeted over the last few years, making it possible for anyone interested in the technology to bring a 3D printer into their workplace, their classroom, or even their home. Using these printers, artists, inventors, and hobbyists are making things that would have been impossible to conceive just a few years ago.

But the sudden accessibility of 3D printers has distracted us from some of the risks of this technology. And different types of 3D printers have very different risks.

The most common type of 3D printer uses a solid plastic filament. Like a robotic hot glue gun, these printers melt the filament and squirt it out into the desired shape. These filament-based printers are not without risks: research shows that they can release toxic vapors and tiny airborne particles while operating. However, most of these risks can be mitigated by simply running the printer in a well-ventilated room, and I’m comfortable having my filament-based printer operating in my garage.

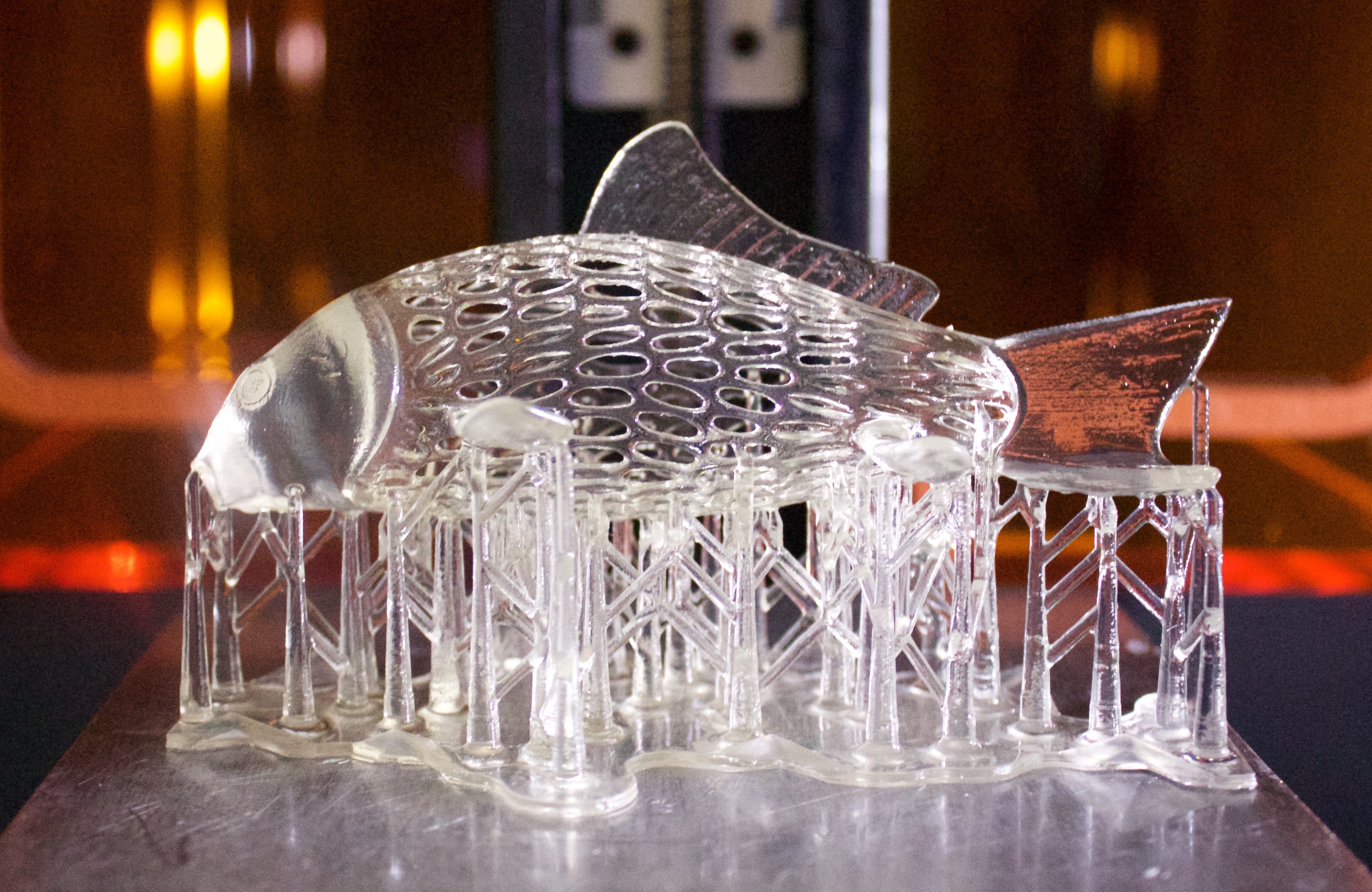

But there’s another type of 3D printer that’s increasingly popular and presents a very different set of risks. Instead of a solid filament, these printers use a thick and sticky liquid called resin. This resin contains a complex mixture of chemicals that turn from liquid to solid when light shines on them.

To understand why resin-based printers are different from—and more dangerous than—filament-based printers, a quick chemistry lesson is in order.

Melting a plastic filament is an example of a physical change, not a chemical change. This means that parts made by a filament-based 3D printer are chemically the same as the filament used to make them. And since the filament doesn’t have to change chemically, it can be made out of common nontoxic plastics like the ones used to make plastic cups and toys.

But in contrast, shining light on a liquid resin to turn it solid is an example of a chemical change—a chemical reaction. A resin-based printer is like a tiny chemical plant, performing chemical reactions that convert a complex mixture of liquid chemicals into a solid. And if the reactions don’t work perfectly, then there’s a good chance that some leftover resin chemicals will remain in the solid part.

In 2015, my UC Riverside colleagues and I studied the toxicity of 3D-printed parts. We found that parts from resin-based printers are much more toxic to living organisms than parts from filament-based printers because of leftover chemicals from the resin. Thankfully, at that time, resin-based 3D printers were considerably more expensive than filament-based printers, so the overall risk from at-home resin printers was relatively low.

Unfortunately, that’s no longer the case. Currently, the top resin-based 3D printer on Amazon.com is actually cheaper than the top filament-based printer. You can have your own resin-based 3D printer for just around $200, with resin going for about $15 a pint.

And while getting a resin-based 3D printer is easy, using it safely isn’t.

Like a newborn alien in a movie, solid parts emerge from these printers coated in a toxic residue of liquid resin. Before the part can be used, this resin must be rinsed off, usually using copious amounts of a solvent like isopropyl alcohol. This generates gallons of resin-contaminated solvent waste.

When I use my resin-based 3D printer in my research lab at UC Riverside, I have to bottle up and dispose of my printer byproducts as hazardous waste. But what can the owner of a resin-based printer do with this waste at home? When asked in online forums what they do with their printer waste, some resin printer users say they “flush it down the toilet,” “pour it in the backyard,” or “set it on fire!” And even if a user knows that 3D printer waste is hazardous, few home users know how to properly get rid of that waste.

So how can we encourage the spread of 3D printing technology while limiting the risk to ourselves and our environment?

First, municipalities need to include resin-based 3D printer wastes in their hazardous material collection programs. My informal survey of SoCal sanitation agency websites revealed detailed instructions on where to dispose of everything from antifreeze to fluorescent lightbulbs, but no guidance specific to 3D printer waste.

Second, if you already have a resin-based 3D printer, make sure you’re using it as safely as possible. That includes locating the printer in a well-ventilated space, wearing chemical-resistant gloves and eye protection when adding resin or rinsing a part, and not placing 3D-printed parts in contact with food or drink.

Finally, anyone in the market for a 3D printer should purchase the least toxic type of 3D printer that’s suitable for their needs. For hobbyists at home, a filament-based 3D printer is far safer and more convenient than a resin-based printer. Schools, libraries, makerspaces, and other purchasers of 3D printers should likewise avoid resin-based printers unless they are confident that they have the safety training and infrastructure needed to use these printers and dispose of their waste properly.