Fun with Python's sys.getrefcount()

Python has a function called sys.getrefcount() that tells you the reference count of an object. For example, the following code,

import sys

print sys.getrefcount(24601)

has the output

3

That basically means that 3 things in Python currently have the integer value 24601. Why would Python keep track of how many things have a value that’s a particular integer? Since integers are one of the immutable data types in Python, Python can save computing resources by having all the variables that contain 24601 refer to the same data in the computer’s memory. For example, if we keep running the above and now assign 24601 to the variable foo like this:

foo = 24601

print sys.getrefcount(24601)

the output is now

4

because we’ve now created another variable with a value of 24601. We didn’t dedicate any new memory to storing the value 24601; we just created a new reference to the same memory that already contained 24601. And if we change the value of foo to be something other than 24601, like this:

foo = 12345

print sys.getrefcount(24601)

the output is back to

3

meaning that Python got rid of the unneeded reference to 24601 (and made a new reference to 12345).

In my experience, 3 is the smallest number of references that I ever get out of sys.getrefcount(). It’s greater than 1 because it includes temporary references created when sys.getrefcount is called. Receiving 3 from sys.getrefcount(number) basically means that number is used in your current code but isn’t used anywhere else in Python. So based on our experiments above, it looks like the integer 24601 isn’t used anywhere by default in Python.

What happens if we run sys.getrefcount() on some smaller integers?

import sys

print sys.getrefcount(1)

print sys.getrefcount(2)

print sys.getrefcount(3)

593

87

28

meaning that, in Python on my computer at this time, there are 593 references to the integer 1, 87 references to 2, and 28 references to 3! This means that these small integers are used elsewhere in Python (i.e., in the guts of the program); there are lots of internal Python variables that contain 1, and many (but fewer) variables that contain 2 or 3. I thought that this gave a pretty interesting insight into the guts of Python, and it raised some interesting questions: which integers are most commonly used in Python’s internals? Which ones are least common?

To find out, I wrote a little Python program that uses matplotlib to plot sys.getrefcount(x) for different integer values of x. This requires that we import the matplotlib package, and when we do, the numbers reported by sys.getrefcount() increase because they now also contain all the references to 1, 2, and 3 in the matplotlib package:

import sys

import matplotlib

print sys.getrefcount(1)

print sys.getrefcount(2)

print sys.getrefcount(3)

now outputs

1910

727

250

In other words, the act of merely importing matplotlib (not actually using it to plot yet!) increases the number of references to the integer 1 by a factor of 3, increases the references to the integer 2 by a factor of 8, and increases the references to the integer 3 by a factor of 9.

Here’s the full code for plotting the output of sys.getrefcount() for every integer from 1 to 1000:

import sys

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

x = range(1000)

y = [sys.getrefcount(i) for i in x]

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

plt.plot(x, y, '.')

ax.set_xlabel("number")

ax.set_ylabel("sys.getrefcount(number)")

plt.show()

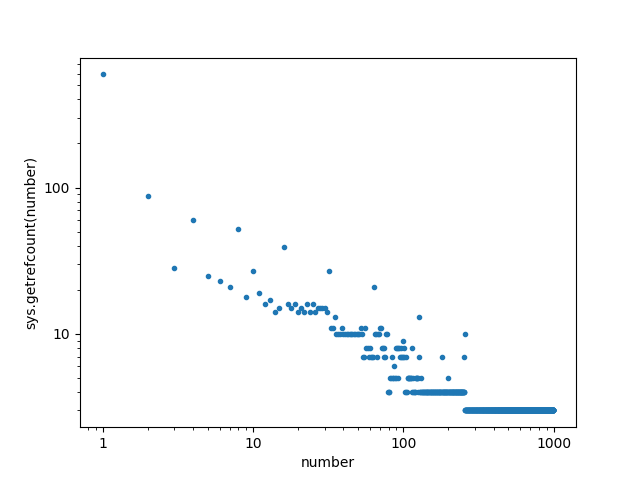

and here’s the output:

Clearly there are many more references to the small integers than the large integers in Python and matplotlib, but there are at least a couple outlier integers with unexpectedly large numbers of references. More on that in a second…

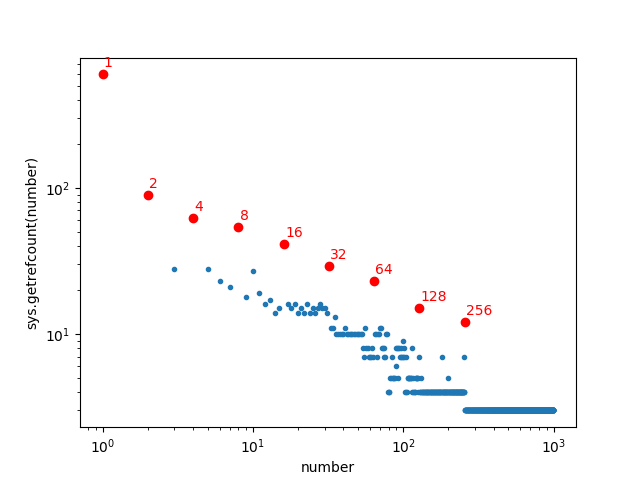

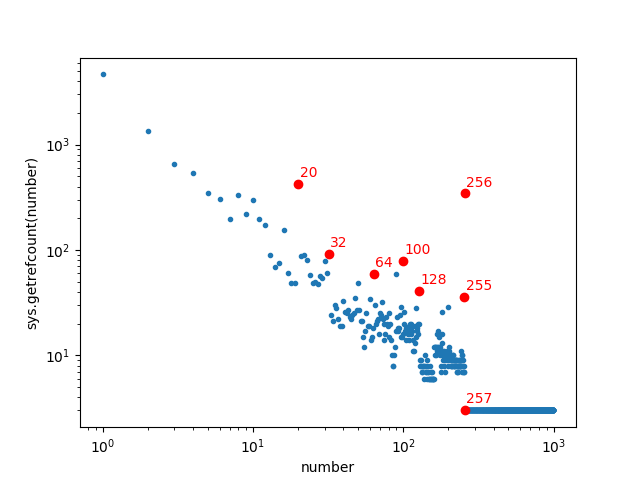

The data looked like it might benefit from a log-log plot, so I made one:

import sys

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import matplotlib.ticker

x = range(1000)

y = [sys.getrefcount(i) for i in x]

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

plt.loglog(x, y, '.')

ax.set_xlabel("number")

ax.set_ylabel("sys.getrefcount(number)")

ax.get_xaxis().set_major_formatter(matplotlib.ticker.ScalarFormatter())

ax.get_yaxis().set_major_formatter(matplotlib.ticker.ScalarFormatter())

plt.show()

Perhaps the most striking thing about this plot is that for integers above about 250, the number of references to those integers drops to a constant 3, meaning that there are no other references to those integers anywhere else in Python or matplotlib. But for the integers less that about 250, the smaller integers are generally used more in Python than the larger integers.

To identify the outliers in this plot (the integers that are used more than would be expected), I made a souped-up version of the plot that annotates the outlier integers:

import sys

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import matplotlib.ticker

x = range(1000)

y = [sys.getrefcount(i) for i in x]

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

plt.loglog(x, y, '.')

ax.set_xlabel("number")

ax.set_ylabel("sys.getrefcount(number)")

ax.get_xaxis().set_major_formatter(matplotlib.ticker.ScalarFormatter())

ax.get_yaxis().set_major_formatter(matplotlib.ticker.ScalarFormatter())

for n in [20, 32, 64, 100, 128, 255, 256, 257]:

ax.annotate(str(n), color="r", xy=(n, y[n]),

xytext=(1, 5), textcoords='offset points')

plt.loglog(n, y[n], "ro")

plt.show()

The results provide a pretty interesting insight into which integers are used most often in a program. The biggest outliers are powers of two. The integer 256 (or 2^8) is used about 100 times more often than would be expected by its position on the number line. The integers 32 (2^5), 64 (2^6), and 128 (2^7) are also clearly encountered more often than expected. This reflects the importance of powers-of-two in many computations. But a few outliers are harder to explain. The integer 100 occurs about 10 times more often than would be expected - why? Because 100 is a nice round number? And the integer 20 occurs about 5 times more often than would be expected; I can’t think of any explanation for 20 being such a popular integer in the Python and matplotlib internals.

We can also see that from 257 onward, sys.getrefcount() returns only 3, meaning that Python doesn’t automatically share references to integers past 257. This doesn’t mean that integers greater than 257 aren’t used anywhere in Python’s internals, but it means that they are used so infrequently that Python doesn’t think it is worthwhile to share references to those integers. You can actually see the number 257 specified as the constant NSMALLPOSINTS in the C source code for Python. Looking at the plot above, 257 seems like an excellent choice for this cutoff; the integers above about 200 are mostly being used in less than 10 places in Python (except for the outliers 255 and 256) so sharing references to these integers will be less effective.

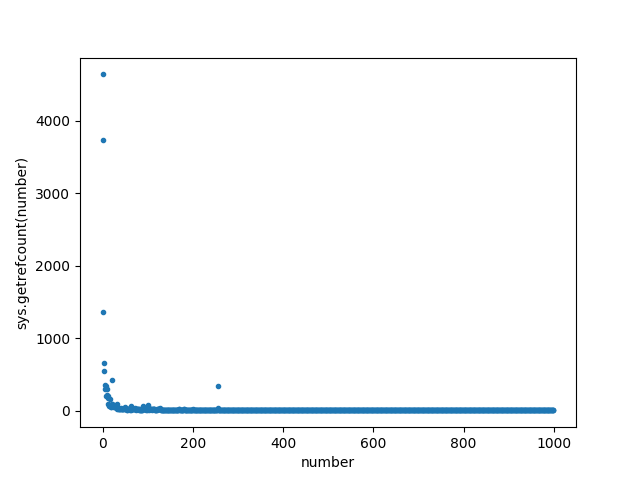

EDIT: Reddit user novel_yet_trivial suggested an edit that plots just the integers used by Python (and not

matplotlib). Here’s the result:

This shows that the extra references for 100 and 20 were entirely due to

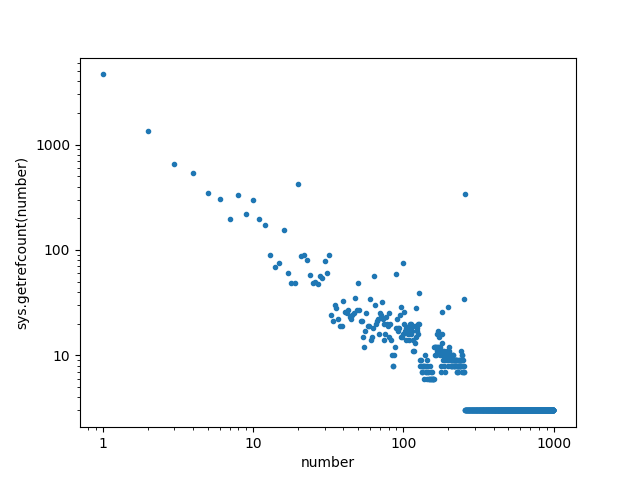

matplotlib(it doesn’t explain why those numbers are favored so much inmatplotlib, though). But even better, it also shows how dominant all the powers-of-two are in core Python. Here’s a version of novel_yet_trivial’s plot with all the powers-of-two annotated:

I love how each power-of-two is more commonly referenced than the surrounding numbers, and even within the powers-of-two the trend of “smaller integers are referenced more” holds true from 1 all the way to 256.

Our fun with sys.getrefcount() can extend beyond integers! Strings are also immutable in Python, and Python uses the same trick with strings as with integers to conserve computing resources. Here’s a tiny program that prints the number of references to the single-character strings from "a" to "z":

import sys

letters = "abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz"

for l in letters:

print l, sys.getrefcount(l)

a 11

b 9

c 16

d 8

e 11

f 15

g 6

h 6

i 33

j 8

k 17

l 12

m 16

n 13

o 4

p 28

q 7

r 7

s 19

t 9

u 5

v 22

w 9

x 11

y 4

z 5

Here I’m intentionally not yet importing matplotlib (and therefore not plotting) to focus just on the strings used by the internals of Python by itself. The most-used single-character lower-case string in Python is "i" with 33 references. I guess this reflects the popularity of "i" as a generic name for an integer, used for example in parsing printf()-style format strings in Python. Second is "p" with 28 references, and I’ve got no idea why. The least common single-character strings are "o" (maybe avoided for fear of looking like a zero?) and "y" (why?).

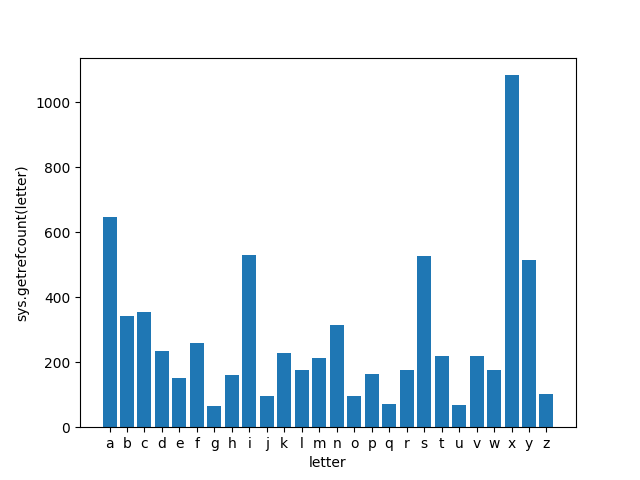

If we import matplotlib to make a nice plot of single-character string frequencies, the numbers change dramatically because of additional use of these strings in matplotlib (which adds thousands of references to these strings):

import sys

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

letters = "abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz"

refs = [sys.getrefcount(l) for l in letters]

y_pos = range(len(letters))

plt.bar(y_pos, refs, align='center')

plt.xticks(y_pos, letters)

plt.xlabel("letter")

plt.ylabel('sys.getrefcount(letter)')

plt.show()

After importing matplotlib, the most common single-character string is now "x", which is almost twice as common as the second-most-common letter and surely reflects the importance of the strings "x" and "y" when plotting on Cartesian coordinates. "a", "i", "s", and "y" round out the top five.

Doing this for strings larger than single characters is tricky; I wasn’t able to use concatenation or list comprehensions to generate these strings and still have sys.getrefcount() work as expected. But you can still run sys.getrefcount() on some possible strings of interest:

import sys

for w in ["RandomJunkBlahBlah", "python", "version", "error", "Guido"]:

print w, sys.getrefcount(w)

RandomJunkBlahBlah 5

python 7

version 11

error 49

Guido 5

Now the smallest value returned by sys.getrefcount() for a string is 5 (returned for the highly improbable string "RandomJunkBlahBlah"). If we subtract 5 from the remaining results, we find that the string "python" is referenced in 2 places by Python, "version" is referenced in 6 places, "error" in 44 places, and the first name of Python’s benevolent dictator for life is referenced absolutely nowhere in Python. Now that’s a shame…