Rife

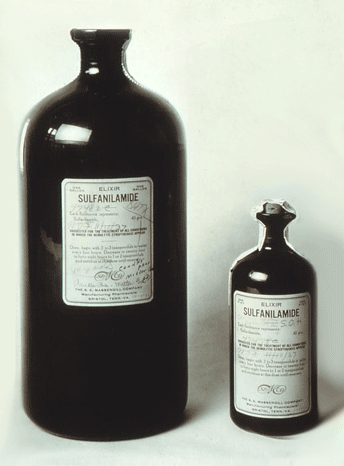

For some reason, the story of the Elixir Sulfanilamide disaster has always fascinated me. If you don’t already know about it, Elixir Sulfanilamide was a drug developed in 1937 by the S. E. Massengill Company of Bristol, Tennessee. Only a month after Massengill began selling it, reports started coming in of patients who endured terribly painful deaths after taking the medicine. Thanks to a herculean effort by the US Food and Drug Administration to collect the remaining bottles of the medicine before anyone else took it, “only” about a hundred deaths were attributed to the drug.

Part of my fascination with Elixir Sulfanilamide stems from the fact that I grew up right down the road from the company that created the deadly drug. Bristol is about 25 miles from my childhood home in Johnson City, Tennessee, and I have vivid memories of seeing the Massengill Company’s factory on family trips to Bristol. I also remember the Massengill Family Monument in Johnson City, a marble memorial to the early Tennessee pioneer family whose descendants founded the pharmaceutical company.

What I don’t remember is ever hearing about the Massengill Company’s deadly product Elixir Sulfanilamide, or the national outcry that followed the deaths caused by Massengill’s drug.

I was born 40 years after the disaster, which isn’t that much time, especially in a small Southern town where even today everyone seems to know everyone else. And at the time of the disaster, S. E. Massengill had over 200 employees in Bristol. It’s reasonable to think that many of those employees were still around when I was growing up. Maybe some of them even remembered Harold Watkins, the chemist at Massengill who decided to use diethylene glycol in the formulation for Massengill’s newest product, Elixir Sulfanilamide. Watkins used diethylene glycol because it successfully dissolved sulfanilamide and had a sweet taste—a bonus for a drug that would be raspberry flavored and suitable for children. What Watkins didn’t know was that diethylene glycol is acutely toxic and can cause kidney damage or failure. But the S. E. Massengill Company didn’t test the safety of Watkins’ concoction—they weren’t required to, legally speaking.

If I did grow up around people who knew the story of the Elixir Sulfanilamide disaster, those people weren’t talking about it. And maybe that’s understandable. In the months after the disaster, newspapers across the country reported on the drug’s victims, often children, who died under what the FDA later described as “intense and unrelenting pain.” In a widely-read letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, one mother described her daughter’s “little body tossing to and fro… that little voice screaming with pain and it seems as though it would drive me insane.” The disaster was apparently too much for chemist Harold Watkins: he killed himself a few months later. So maybe it’s understandable that a company—and a community—would want to put this story behind them. Maybe that’s why I spent the first eighteen years of my life just a few miles from the company responsible for one of the deadliest poisonings in American history but I only learned about the disaster years after leaving home.

But while S. E. Massengill’s employees may have been reluctant to discuss the Elixir Sulfanilamide disaster, the owner of the company did have a few things to say. In another widely-reported quote, the eponymous Samuel Evans Massengill stated that

My chemists and I deeply regret the fatal results, but there was no error in the manufacture of the product. We have been supplying a legitimate professional demand and not once could have foreseen the unlooked-for results. I do not feel that there was any responsibility on our part.

I teach a class on medical diagnostics every year at UC Riverside, and in that class we discuss the Elixir Sulfanilamide disaster. Every year I read Samuel Massengill’s quote to the students, and invariably they are left with wide eyes after hearing it. In particular, it’s Massengill’s claim that the company could not have foreseen “unlooked-for results” that is the most jarring. Massengill’s defense is that they couldn’t find something that they didn’t look for. And since, in 1937, Massengill’s company wasn’t legally required to look for potential toxicity, they didn’t. He was right that the company bore no responsibility for the tragedy, at least from a legal perspective. In fact, the FDA was able to recall Elixir Sulfanilamide not because it was a poison, but because it was mislabeled: an “elixir” must contain ethanol, and Elixir Sulfanilamide did not. If the drug had been named “Solution of Sulfanilamide,” the FDA would likely have had no legal authority to recall the deadly drug.

The fact that a pharmaceutical company could sell a deadly poison as a drug and not even break the law incensed the public. Mere months later—working at a pace that’s almost unfathomable today—Congress passed the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938. The FD&C Act gave the FDA the authority to oversee the safety of pharmaceuticals. Under the Act, companies like S. E. Massengill would have to perform animal testing of a new drug and submit the results to the FDA before they could sell the drug.

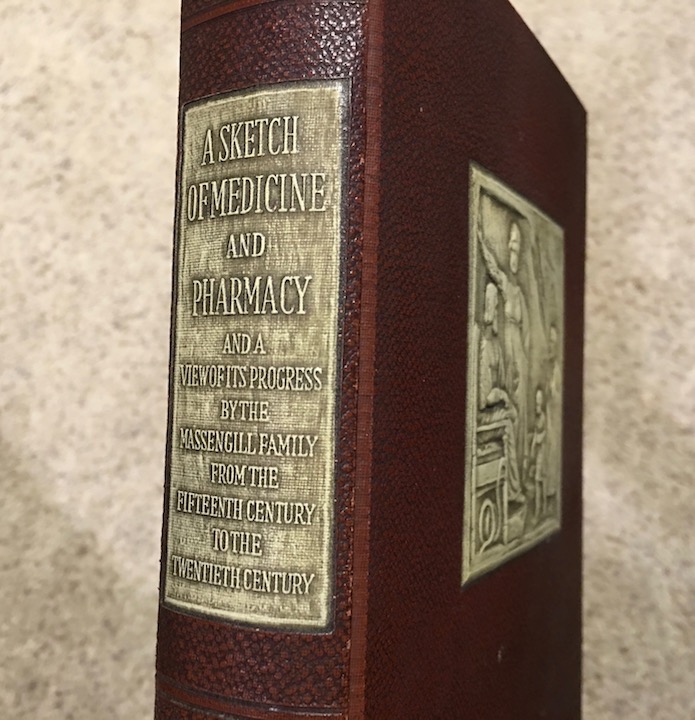

Samuel Massengill’s company was to a large extent responsible for the creation of the FD&C Act. And that is why a passage in a book written by Massengill recently caught my attention.

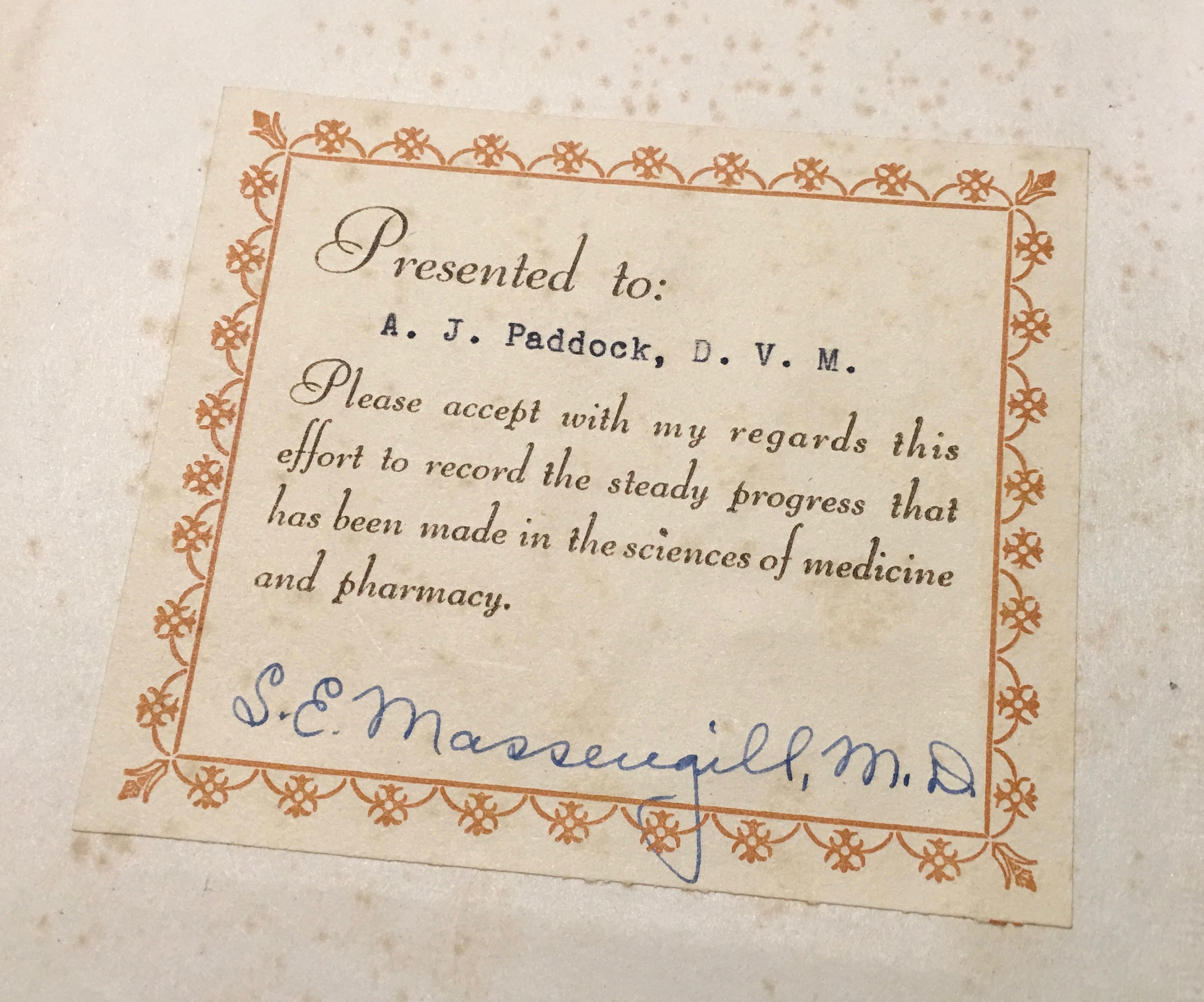

The book is entitled “A Sketch of Medicine and Pharmacy,” and my copy has a copyright date of 1942, just five years after the Elixir Sulfanilamide disaster. My copy is inscribed to a doctor of veterinary medicine and signed by Massengill himself, but it is not as special as it sounds—a handful of similarly signed and inscribed copies are available for sale on eBay, and one suspects that Massengill sent copies to all his clients.

The book contains mostly a rambling collection of anecdotes on the history of medicine, including chapters on “Medicine in the Bible” and “Snakes in medicine.” Massengill spends a somewhat disproportionate amount of time in the book on poisons, including a survey of famous poisoners throughout history. Altogether, 50 of the book’s 400-some pages deal with poison, and it is hard to read these pages without remembering that just five years before they were published, the writer was disavowing responsibility for the deaths of over 100 patients who consumed a poison with the writer’s name on the bottle.

But it is a single sentence at the end of Massengill’s chapter on “Pharmacy” that really caught my eye. On page 403, Massengill writes

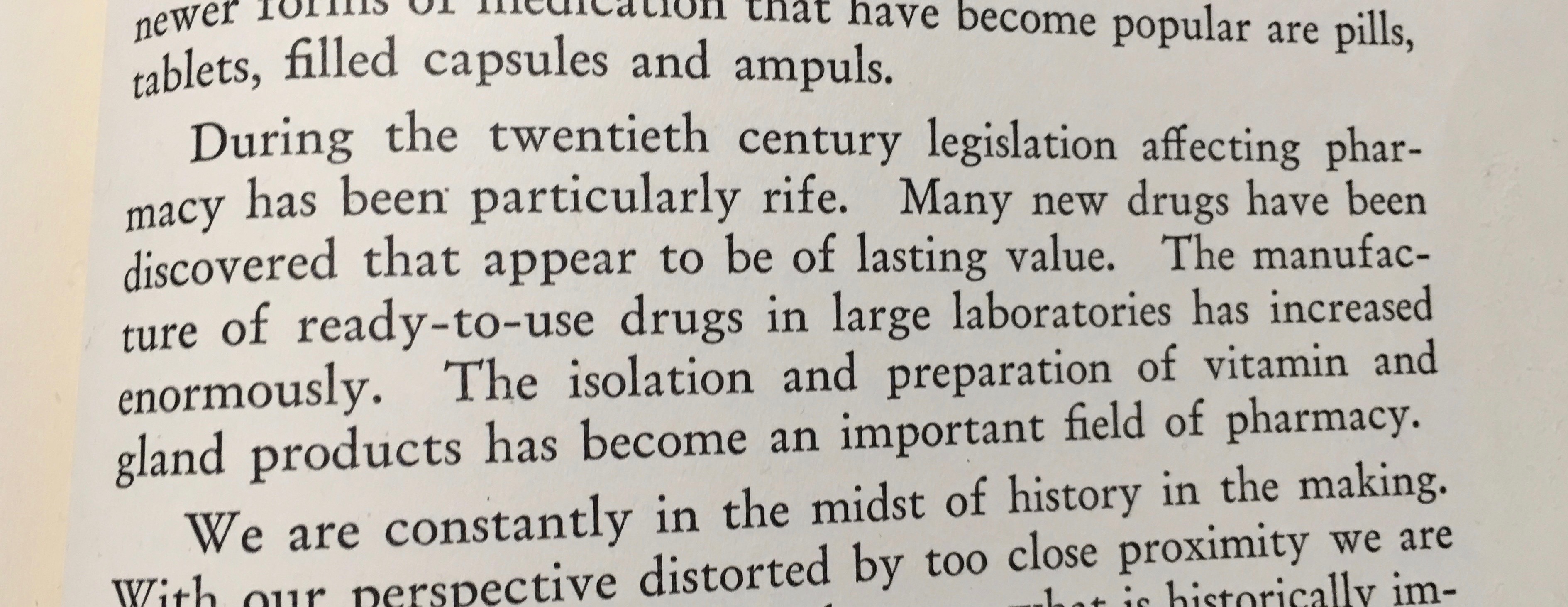

During the twentieth century legislation affecting pharmacy has been particularly rife.

The FD&C Act is without a doubt the most important single piece of “twentieth century legislation affecting pharmacy,” and it was passed only four years before the book was published, so it seems safe to assume that Massengill is referring to the FD&C Act. But as for the rest of the sentence, “rife” immediately stood out. “Rife” had an immediate negative connotation to me. I thought it described something widespread and bad, like saying “Paris is rife with pickpockets.”

Was Samuel Massengill really calling the emergence of laws protecting the consumers of pharmaceuticals a bad thing? Just five years after his own company fatally poisoned a hundred of those consumers?

The context of the sentence doesn’t help much. The preceding paragraph describes using capsules to mask the unpleasant taste of drugs. But the sentences following Massengill’s “rife” comment might provide some illumination:

Many new drugs have been discovered that appear to be of lasting value. The manufacture of ready-to-use drugs in large laboratories has increased enormously.

These “new drugs” of “lasting value” had to be tested for their safety because of the “particularly rife” new legislation.

At this point, I started wondering if I misunderstood the meaning of the word “rife.” Maybe it wasn’t as negative as I thought? So I consulted a few dictionaries, and the results confirmed my preconceptions on the word. Merriam-Webster defines “rife” as “very common and often bad or unpleasant” and offers a sample usage by W.E.B. DuBois: “Suspicion and cruelty were rife.” Not exactly a positive word. The Cambridge Academic Content Dictionary offers additional examples: “Graft and corruption were rife in city government.” “The office is rife with rumors that many of us will be fired.” Again, a pretty negative take on whatever is described as “rife.” But maybe it meant something different back in the 1940s when Massengill’s book was published? Well, Webster’s 1828 dictionary says that rife is “used of epidemic diseases” and offers up the example “The plague was then rife in Hungary.” Once again, not a positive term.

So it seems that Samuel Massengill really was describing the FD&C Act using a term usually reserved for corruption and epidemic diseases.

If you look hard enough, you can find a handful of usages of “rife” that are non-negative and merely connote a “proliferation.” But even that interpretation of Massengill’s “rife” is problematic. Before 1938—before the Elixir Sulfanilamide disaster—there was not a “proliferation” of legislation about pharmaceuticals. There was mostly just the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, which required that drug labels accurately reflect the drug’s contents but did nothing to guarantee the safety of the drug. In 1938 the FD&C Act was passed, but it was only four years old when Massengill’s book was published, and though the FD&C Act would be amended many times, the first of these amendments came nine years after Massengill’s book was published.

In short, the years before Massengill’s book was published were not “rife” with pharmaceutical legislation, and this is precisely why Massengill’s company was able to fatally poison 100 people without criminal negligence. If these years had been more “rife” with legislation, then the Elixir Sulfanilamide disaster might not have happened.

Samuel Massengill concludes his “Pharmacy” chapter with this comment:

We are constantly in the midst of history in the making. With our perspective distorted by too close proximity we are usually unable to differentiate between what is historically important and what is not.

On this point, at least, he seems to be correct. Writing just a few years after the Elixir Sulfanilamide disaster, Massengill is too close to see what his ultimate legacy will be. After a series of mergers and acquisitions, the only one of Samuel Massengill’s products that still has his name on it is a brand of vaginal douche. And Samuel Massengill is remembered as the owner of the last pharmaceutical company to poison its customers without breaking the law.